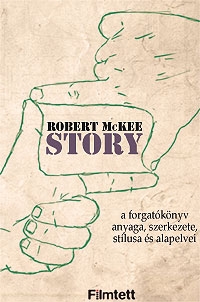

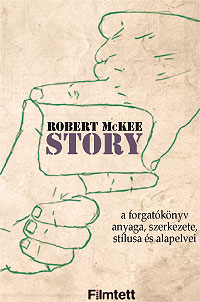

Robert McKee's Story was first published in 1997 - we had to wait 15 years for the Hungarian translation. We picked 71 year old "guru's" brain on this occasion.

What is your opinion about state-run film funding (the common practice in Europe) versus Hollywood-style film industry?

There are two kinds of censorship. Commercial censorship – which Hollywood engages in –, which puts limits on subject matter, often on endings, trying often to discourage tragedy and to create films that are somehow uplifting. In Hollywood and America, there is a tremendous amount of independent filmmaking outside of Hollywood, which is able, on low budgets, to go into these dark corners of human nature, and occasionally make excellent films such as Boys Don’t Cry.

The other kind of censorship – state censorship in which people try to reach state money often censor themselves before submitting their project for funding because they know perfectly well what the government will accept and not accept. Certainly the government in very rare cases will not accept criticism of the government (or deep criticism of the society as a reflection of a poorly managed government), and so writers know they cannot touch those topics. This is one of the reasons we see so little comedy coming out of Europe, because comedy is the

“angry art” that attacks social institutions and social behavior and ridicules power and authority and consequently those films are more difficult to get financed, as state government are not interested in being ridiculed. But nonetheless, courageous filmmakers in the state sponsored system, still make marvelous films, often dark.

The greatest freedom of all right now, and the one with the least amount of censorship and the most encouraging of writers to go into is television. The satellite networks, not necessarily the commercial networks, starting with the famous HBO, Showtime, A&E, are certainly encouraging writers to go in depth.

So state funding, commercial funding, some combination of the two: the main problem for the writers is how to write and make films they really want to make, without having to compromise either the commercial or the state’s considerations.

What about auteur theory? Is it a romantic notion for those nouvelle vague-dreamers or is it viable today? Do you see a conflict between this theory and screenwriting as a separate job?

At its worst, the auteur theory elevates stylistic consistency over content. I have no trouble with the auteur theory if the writer directs the film. If the artist is a writer/director who can create wonderful characters and then direct the actors in those roles, and direct the film to the screen, for me that is not an auteur, that is an author. One of the questionable aspects of the auteur theory is using the French word, so that it has a connotation of not really being an author, but sort of “author-like” or “author-ish”. If we are going to use the word, “author”, then we should insist that they both write and direct.

There are many fallacies in the auteur theory: if directing is the only serious aspect of the auteur work, and the director is really the auteur of the film, then why are directors so inconsistent? Hitchcock is a favorite auteur. He made some wonderful films, like Vertigo, but he also made some very dreadful films like Family Plot. So the difference between one film to another is the writing. Hitchcock couldn’t write. I believe in the “author-ness” of films when they are both written and directed by the same person. Otherwise, I think that we should all understand that film is a collaborative artform and that the director finishes what the writer began, but the original act of creativity in making the film is the writing. The finished work is the difference between a good film and a great film: the director. Why directors then need the auteur theory to elbow the screenwriter out of sight, so that they can bask in the glory of what they do? It’s an embarrassment. As fellow artists, we should all be appreciative of each others’ work and not try to take the constant spotlight for ourselves. Directors who want to be called auteurs when they can’t themselves write, are putting their ego in front of their integrity.

Will the internet kill movies?

No, but it will transform them. I don’t know how long it will take, but I think the cinema will be lost, television and broadcasting as well. People will get their visual storytelling on their cellphones. Like it has already begun in television today, stories are going to get longer and longer. People will be interested in becoming a companion to the characters in stories and bring them into their life, as if they were family as the storytelling goes on for dozens, maybe hundred hours or more. As storytelling gets longer and longer, like in contemporary television series, people will keep them literally in their pocket and watch bits and pieces as they have time and follow these stories for extremely long periods of time. I think that is the future.

How about 3D?

3D is another technical innovation. There already was 3D when I was a boy in the 1950’s, so 3D is at least 60 years. It got boring, because it was so concentrated on action: characters were constantly throwing things at the audience in order to demonstrate the 3D-effect.

But now 3D has become very sophisticated and I have no problem with it. When watching 2D, the mind automatically translates it into 3D. Now, when watching 3D, your mind doesn’t have to do that. So I suppose as long as 3D does not call attention to itself as 3D (if you can watch a 3D film as if it were 2D and just follow the story and the characters and not constantly be distracted by the fact that you are seeing in the third dimension in depth), it’s fine. Because this distraction is irritating and takes away from your concentration of the characters in the story. But when 3D gets to the point where you don’t notice it, what is the point of 3D? The mind will take 2D and turn it into 3D anyway. It is going to take a lot of innovative, concentrated experimentation in the future to find out if 3D really makes any enhancement to the story.

What made you write Story? Were there inspiring works for you about storytelling before that – or rather the lack of those? What do you think of Lajos Egri’s seminal work (The Art of Dramatic Writing) that was used in Hollywood for a long time before Story came along?

I was delivering the Story lecture for many, many years, and my students more or less demanded a book. They wanted to be able to take the lecture with them in book form and to have it as a reference at their elbow the same way like a dictionary. And so it was to fill the needs of my students that I wrote the book.

Lajos Egri, the famous Hungarian theorist, wrote a book about playwriting many years ago (50/60 years). I read it, in my youth, and found it of interest, but I also found it fundamentally flawed. Egri’s writing about character was extremely mistaken. He thought that what makes a great character, is the character who has a dominant trait. For example, the character Macbeth and the trait of ambition. When I read that, I knew that was false. If Macbeth was merely ambitious, there would be no play. He would just take the whole country to himself at short order. But what made Macbeth a great character was the contradiction between his ambition on one hand, and his guilt-ridden conscience. What makes great character is contradiction. We call those contradictions “dimensions”. This is something Egri did not understand. Egri was also “theme-driven”, the thought that a writer could not write until they knew the meaning in advance. My point of view on writing is the opposite of that. Writing is an exploration of life that ultimately at the end of the process, you arrive at a story that expresses to you the meaning that was lurking within your mind but ultimately comes to understanding after or as you finish the work. And so Egri and I have very opposite points of view on writing. I think writing a story is an exploration and he thought that it was a rhetorical proof of a pre-conceived meaning.

Is there something you would add to STORY after 13 years (regarding genres, for example)? Have any great scripts been written since then that you would include?

I am doing a whole new series of books on the genres on LOVE STORY, COMEDY, THRILLER, and ACTION. So there will be at least 4 or 5 books on the genres. I am also doing a book sequel to STORY: ON CHARACTER, as a companion piece to STORY. And someday if I live long enough, I will write STORY 2. This will be twice as big as STORY 1, because it will contain all sorts of material from STORY 1 such as prologues and epilogues and a great deal more about dialogues and many other subjects that were left underdeveloped in STORY, so I have lots of writing ahead.

Is the book meant for those who want to write screenplays? Do you have any feedback from other types of scholars (film theory, film criticism etc.)?

I put the word “screenwriting” in the subtitle of the book and called the book STORY, because if I do, and I hope to do another version of STORY (STORY 2). I will take everything in STORY and find examples from the theatre and from the novel, because story and the principles of storytelling are underlying all the great media for Story and I know from having worked with these writers and novelists and playwrights and people who write the books for musicals that they rely heavily on my book. So it’s a book that although the examples are given in films (because that’s such a common currency for people), writers of all story telling forms use.

Who are you the proudest of among your ‘pupils'?

I don’t single out people for proudest. You can not compare them, because they work in such very different genres. Peter Jackson often works in fantasy, science-fiction. Paul Haggis makes a generally gritty realistic stories, but he wrote one of the very best James Bond-films, Casino Royale. Akiva Goldsman is also a very serious dramatic writer, whereas Zak Penn writes big action films. So I am very proud of all of them. Then there are the television writers who write magnificent television series, like the Kessler brothers and Zelman who wrote this great series, Damages. It’s certainly an apples and oranges thing to compare Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings to a television series like Damages. So there are lots of writers that I am very proud of.

What would be your one-sentence advice to absolute beginners?

Don’t quit… It’s going to take 10 years or more to turn yourself from a beginner to a professional who makes a living of it. If you give up after a year or two, you were never meant to be a writer anyway.

What is your favorite Hungarian film? And Romanian?

Well, the films I know best from Hungary, are those of István Szabó and going back to wonderful pieces like Mephisto, which was such a stunning, marvelous piece of work. Other films like Sunshine, which I thought was nice, I enjoyed it a lot. Being Julia was a delight. These are wonderful films and I’ve seen a number of his that I have enjoyed greatly.

Because Romania has had such a troubled political past, very few films have found their way into the US, the only film I have ever had an opportunity to see was The Way I Spent The End Of The World which I thought was a very moving drama about young people struggling to get out and find a life outside of Romania. It was certainly well told and well made film.

The Hungarian translation of the interview can be read here.